Among the many layers of stereotypes woven into the cobweb that Mumbai’s social structure is, the rickshaw-wallah is a prominent fixture. To most suburban Mumbaikars, the rickshaw-driving community comprise an offensive lot, given their tendency to refuse rides and general recklessness; but its equation with the city and its people is a bitter-sweet (mostly bitter) one. This interdependent relationship is, however, inked indelibly onto our social fabric because of who are as a country – people driven by efficiency. Thus, the autorickshaw is a sort of icon in this bustling society, making life happen at a fast pace, with absolute empathy for your every hard-earned penny.

Bajaj, which has a near-monopoly in the three-wheeled mass transportation space, envisions this reality to be better. The Qute, India’s first quadricycle, it is categorically apart from a car, even though the four-wheel, four-door configuration makes that distinction a bit blurry. It sure looks like a car, albeit a caricature-ish version, but its lines were penned by the humble dreams of a utilitarian mindset. It has a roof and windows to keep out the rain, and a bonnet to protect your luggage from the elements.

The plastic doors are simply a means to keep you from turning into a human cannonball every time (not that you should make a habit of it) you find yourself amidst a collision. I suspect Bajaj wouldn’t even have given the Qute seats, but since there are four of those, you get a seatbelt for each occupant. Yes, it’s that elementary in its premise. And the engine? That’s just as elementary! It’s a 216cc, twin-spark, liquid-cooled, single-cylinder motor fed by CNG (or petrol), developing a modest 11hp (13.2hp in the petrol-only variant). That calls for modest stopping power and so, there are no discs but only drum brakes housed within the four 12-inch wheels.

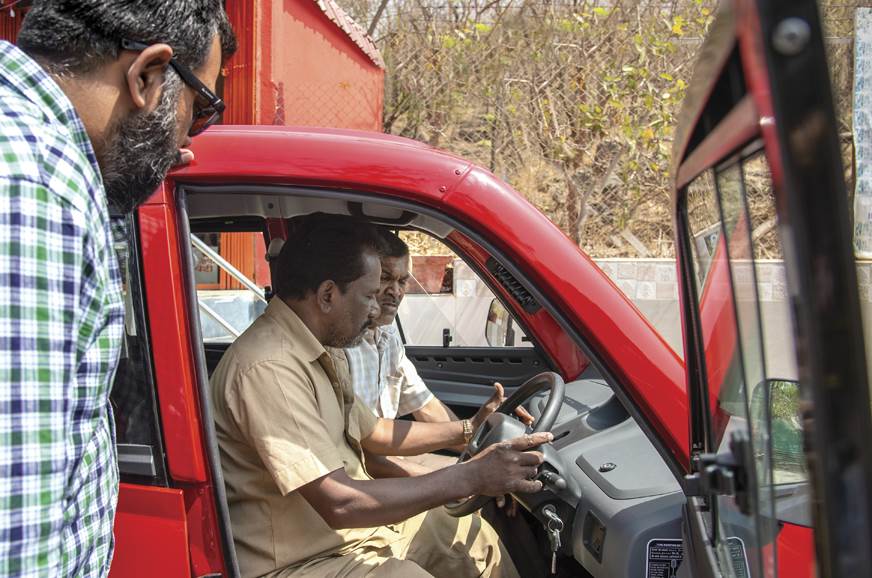

In about a minute of having parked the Qute head-on against a Bajaj RE four-stroke rick – a bit confrontational, in hindsight – I became part of a khaki-clad huddle. Before I knew it, I was driving three men I’d met only minutes ago up a hillock. I was to demonstrate the Qute’s 18 percent gradeabilty (the CNG version can go up a 10.2 degree slope; the petrol version does 11.3), and determined to not be embarrassed by people I hardly knew, I chose the first of five gears and a heavy throttle foot to shield my pride. To my surprise, and theirs too, we were soon in a state of brisk forward motion, enough to inspire me to shift up the gearbox. Later, the 3.5m turning radius left them just short of applauding in unison, and that steering was the job of a wheel than a handlebar was a matter of evolution for them. I went on to learn that the average 10hr work shift of a rickshaw driver leaves his arms particularly sore, because of the constant steering effort that the job demands.

Over the next hour or so, we kept pace with flowing city traffic, swiftly braked to abrupt halts (happens a lot in Pune) and even deliberately ignored speed-breakers, but the Qute took it all in its stride. Over a round of chai, the rickshaw drivers told me why they’d like to see this as their future. That it is more comfortable to drive than a rickshaw, can seat four comfortably, is structurally more refined (and therefore, more durable) than a rickshaw, and it offers a large, 8kg CNG tank (halving the time spent in queues) in addition to an 8-litre petrol tank spells profitability in every sense. In other words, the Qute isn’t just cost-efficient but time-efficient, too. Its party-piece, however, is the running cost; with a claimed fuel-efficiency figure of 45km/kg for the CNG variant, the Qute racks up a per kilometre running cost of Rs 1.53 – that’s Rs 0.09 higher than a Bajaj RE rickshaw – and, shockingly, over a rupee cheaper than the average motorcycle! The petrol-only version is at par with, say, a Wagon R CNG in this aspect but then the Qute’s 35kpl claimed fuel-efficiency figure and intra-city convenience still give the quadricycle that crucial edge in this cut-throat business.

It is in the personal mobility aspect that the Qute under-delivers. To be fair and logical, the Qute is an ideal and relatively safer alternative to a scooter, but it will take a strong evolution for it to appeal to entry-level car buyers. Its city-only application is just a part of the concern. The bigger problem is how austere it is and that for the same price, you could have an Alto 800 which is a proper car. Bajaj has addressed ventilation to some extent, with an A-pillar duct being a recent and helpful addition, but the lack of a blower (forget air con) and the sliding windows aren’t exactly in sync with the times. Another aspect to consider is that India, as a society, still considers cars as a status symbol and, in that scheme of things, the Qute is the equivalent of telling your neighbours in a high-pitched voice, that you are, well, poor.

In more evolved markets, like Europe, for instance, the Qute will find takers (or possibly, even spawn a cult following) but in the Indian context, it’s not going to establish itself as a VW Beetle of the new millennium – not in its existing form, at least. Having said that, if the Qute was designed a bit classically – like, say, a Beetle or a Fiat 500 – it would tempt at least a sliver of conventional car buyers. Indeed, it has immense potential to be a four-wheeled Vespa of sorts, and I hope Bajaj takes the chance.

On balance, the Qute can establish itself based on its existing merits, too, but a cheaper acquisition cost, to both, private and commercial customers, will do it immense favours. Right now, it’s good-hearted and functional; but perhaps a bit too optimistically priced to really bring about change in the world.

[“source=autocarindia”]